I had downloaded the BBC Reith Lectures, which this year featured Margaret MacMillan discussing the complex relationship between Humanity and War. At one of the Q and A sessions after the War and Art lecture, she was asked her views on the recent campaign to remove prominent Civil War statues in the U.S. She said that this issue can be viewed in a number of ways and that, for example, great art can come from questionable sources citing Richard Wagner and

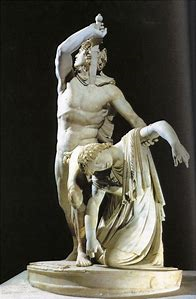

Roman Art to illustrate this. Interestingly, it was only this year that a piece of music composed by Wagner was played over Israeli radio and MacMillan’s argument was made to people who protested against airing the works of a composer so closely associated with the Nazi regime. Art can also reflect subjects that present difficulties for a modern viewer. The Ludovisi statue (opposite) recorded the triumph of the Greeks over the defeated and subjugated Gauls by showing the double suicide of a defeated Gaul couple who preferred death to capture and slavery. Time is obviously a factor in how we interpret art and the Roman copy of the Greek statue, said to be entitled The Galatian Suicide, is an example where the raw emotion of the piece has been tempered by the passage of time and yet still resonates today.Wagner however, still provokes protest from people who can remember or, are only one generation away from the holocaust. MacMillan suggests a case by case review factoring in the original purpose of the statue. For example, something that commemorated soldiers killed or, past heroes might pass the test but statues erected to reinforce the oppression of a racial minority, particularly those erected in the 1950’s South would not. Of course, this is highly subjective and a review of this kind doesn’t always work in an overheated atmosphere.

Ireland has not escaped the revision of historical monuments and the pictures opposite show two of them. The first , in fairness, only shows half of the original statue after the Nelson Pillar in O’Connell Street was blown up in 1966. The interesting contrast with the intense nature of the Confederate Statues argument was not that it was destroyed, bearing in mind the situation in the North but that it wasn’t replaced by a suitable republican figure. Despite Irelands recent colonial past the Pillar was replaced by the Spire (or the Needle, if you belonged to the illegal substance taking community). There was more annoyance than fervour in the public reaction and the eventual replacement with the Spire was more of an effort to revitalise the city centre than any protest against the past. That there are such sentiments is demonstrated by the petition to move the Statue of Prince Albert, (Above) currently standing in the grounds of Leinster House. That this hasn’t gained much traction was demonstrated by the fact that no one had noticed who it was and that TD’s who attended the Oireachtas on a daily basis, didn’t know where it was until the question arose. The proposal did reach Committee stage until it was discovered that the Parliament didn’t own it and therefore couldn’t remove it. The current thinking is that the previous occupants left it there but there is no political will to progress it any further. The third example of Moving Statues in Ireland is the occurrence of Marian statues that moved spontaneously in the 1980’s which allows me to make a rather weak pun between the text and the title of this essay.

The most recent controversies in the UK have been related to figures that profited from the slave trade and colonialism such as Cecil Rhodes and Edward Colston but it is the statue of Sir Arthur Harris that I have selected to demonstrate that a statue can mean different things to different people. The statue was erected in 1992 and celebrated the head of Bomber Command in the second World War. Historians are still divided by the Area Bombing strategy that he implemented in the belief that it would shorten the war. This is a complex issue but I just want to take three views that prevailed at the time the statue was erected. The first and noisiest were those that believed the policy Harris followed was a war crime, especially the bombing of Dresden carried out in 1945. They argue that Dresden was a low priority target that was subject to massive raids by the USAF and RAF bombers with high levels of civilian loss. The second view was from the survivors of Bomber Command who felt that the discussion over the Bombing offensive obscured the bravery of and huge losses suffered by the aircrew. RAF Bomber Command suffered proportionally higher losses than the other Services and survivors felt that their sacrifices were overshadowed by the more glamorous Fighter Command and the post war debate on bombimg strategy. Thirdly, Harris often quoted a passage from the Old Testament, “They sowed the wind and now they are going to reap the whirlwind.” (Hosea 8-7) This summarised the view of most of the wartime population who had suffered privation, personal loss both in the Services abroad and at home during the Blitz and V1 and V2 campaigns and the real threat of defeat and conquest.

I haven’t made the morale argument in any of the above and have avoided quoting losses or statistics that can be used to make a matrix or hierarchy of suffering to support one argument or another. I have deliberately taken non US examples as, from this distance, I cannot fully appreciate the depth of feeling of all those who have taken sides in the US Statues debate. I also understand that in most cases where statues have been removed they have been relocated to Confederate Cemeteries or other suitable locations. From this can we assume that the objective is not to eliminate past record but to remove currant flashpoints? It would be interesting

to know whether that assumption can be sustained. What you see on the news are very angry people targeting statues like the one in California, featuring a native American at the feet of a cowboy and a missionary, entitled Early Days. Surely statues like this can have no place in modern life? Yet it took some time for the decision to be made to move it and a defense was made by comparing the removal with the destruction of past icons by the Taliban and the book burning of the Nazis. The timing of the protests may be as a result of other factors coming together such as the #MeToo, LGBTQ and Black Lives Matter movements creating an environment where establishment icons are sought out and challenged. It is interesting that statues are the selected targets and that they still have the power to excite this level of attention. It is this point that Professor Madge Dresser makes in her discussion of the current events. She states the following,

“Statues are lightning rods, symbols of the prevailing values of the society. When those values are not shared a debate needs to be started.” (BBC News Magazine, 23/12/15)

The description of a lightning rod seems appropriate as we attach current issues around racism, in this case, and try to ground them in the past. Why the current protests should be so visceral in the US and relatively calm in Ireland and the UK is a matter of debate. Certainly, the issues around slavery, the Civil War and current politics haven’t been resolved in the States. Ireland has also only recently, in historical terms, had their own War of Independence and Civil War with huge issues still to be resolved in the North but do not seem to have followed the same route as their US contemporaries. This may be down to different historical trajectories and is not the debate here. If we take Professor Dresser’s view that a statue can represent past and present values, then she argues that they should be preserved in most cases (Unsure about the Early Days statue) and the different view points should be expressed in the tablet fixed to the statue. As she says, “To take the example of Colston in Bristol, the current positive plaque on his statue could be replaced by one that made clear that he was involved in the slave trade. Thus a debate could be started. “It’s better on the whole to keep the statues but to recontextualise them.”

In the end there are many variables that make up the debate and the value of these historical icons is that they visually record historical revisionisms that reflect the different values in society over time. That some statues are just bad art I will leave to those with better taste than I have to decide. However, given the ever changing Art scene, perhaps they should also be stored under the stopped clock being right twice a day principle. Professor Dresser acknowledges that keeping statues of Hitler may be too controversial but many of those statues under threat have a different story to tell other than the one portrayed today as is the case with Marshal Harris. At a time when political analysis is made by sound bite and social commentary reduced to single word terms of abuse we have to preserve our ability to rationally debate difficult and complex issues. There is a movement to prevent a statue of the famous Indian pacifist, Mahatma Gandhi being erected in Malawi (Times 16/10/18). Surely this is a man above reproach, yet the ‘Gandhi Must Fall’ group accuse him of racism to black Africans and the novelist Arundhati Roy claims he supported the caste system in India. The lesson to take from all of this is that the world is a complicated place. Good people are rarely good all their lives. Indeed the definition of what is good differs over time and we need to do more than shout slogans and impose our ideology on others to understand the past and the present. Perhaps statues have a bigger role than we thought and by a study of what they meant in the past our opinions, so strongly held today, might be challenged. I suspect that those who shout the loudest do not want to listen to the stories that the statues have to tell, which is why it is even more important that the rest of us take the trouble to do so.

We are not makers of history. We are made by history. (Martin Luther King)

References: When is it Right to Remove a Statue, Finlo Rohrer, BBC News Magazine, 23/12/15, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-35161671 The Reith Lectures, 2018, Margaret MacMillian, BBC Radio 4, Producer Jim Frank. The Times, 16/10/18, Jane Flanagan, Gandhi Must Fall. https://www.brainyquote.com/topics/history