I have avoided writing a commentary on Brexit, partly because of it’s complexity and partly because the debate centres around fault lines rather than the underlying fundamental issues. I was sent the following article, written by George Friedman and it became clear that Charles De Gaul understood and predicted the current crisis. What it says is that you must understand what has happened in the past before you can explain the present. There are a number of things that De Gaulle got wrong but overall he put historical context first and this is what I think the debate should be about.

I have avoided writing a commentary on Brexit, partly because of it’s complexity and partly because the debate centres around fault lines rather than the underlying fundamental issues. I was sent the following article, written by George Friedman and it became clear that Charles De Gaul understood and predicted the current crisis. What it says is that you must understand what has happened in the past before you can explain the present. There are a number of things that De Gaulle got wrong but overall he put historical context first and this is what I think the debate should be about.

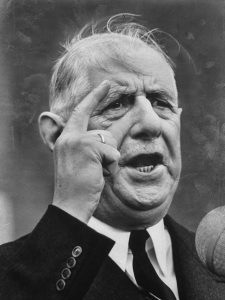

Brexit and Charles de Gaulle’s Last Laugh

In many ways, de Gaulle foresaw the crisis Britain is now struggling to pull itself out of.

As we watch the British government tear itself apart over its relationship to Europe, it is useful to stop and consider the deeper origins of the crisis. They go back decades, to the long-standing tension between Britain and Europe, and in particular between Britain and France. Britain was not a signatory of the 1957 Treaty of Rome or any of the prior agreements that led to European economic integration. But in the 1960s, it applied to join the European Economic Community. At the time, Britain was economically weak, having never fully recovered after World War II, and saw the EEC as a free trade zone with relatively few complexities. The country had stayed clear of excessive entanglement with continental Europe but felt that having less limited access to Continental markets would help in its recovery.

But the British application to join the EEC was blocked by France in 1963 and 1967. French President Charles de Gaulle argued that the British economy was in many ways incompatible with the rest of Europe’s. He also argued that Britain had a deep-seated animosity toward any pan-European undertaking and would perceive a united Europe as a threat to its independence. De Gaulle didn’t view Britain as a fully European country, since its history ran counter to Europe’s history. Since the Norman conquests, Britain had been fencing with Continental powers, playing one off against the other to prevent any one power from becoming strong enough to storm the English Channel and conquer it. Whereas the other European powers were primarily land powers, forced by geography to focus on the threats posed by their neighbors, Britain was a naval power, whose primary response to Napoleon, for example, was to protect itself through a blockade that weakened France. From de Gaulle’s point of view, Britain fought World War II the same way – by shielding itself and abandoning France.

The British understanding of economic life, according to de Gaulle, was also incompatible with Europe’s. The British economy was driven by private investment, innovation and risk-taking. Continental economies had a much more intimate relationship with the state, which helped shape the direction of the economy and cushioned the impact of capitalism on workers. The state’s relationship to the market, therefore, was also very different. De Gaulle did not see the state as intruding on the nation but as the embodiment of the nation.

The European Union derives from the same tradition de Gaulle did. Neither objected to private property, but they believed in the need for state intervention in all aspects of life. The EU has a regulatory bent that is far more intense than the British, and sees its bureaucracy as having authority far greater than Britain’s.

De Gaulle had other bones to pick with the British. Britain’s relationship with the United States troubled him deeply. De Gaulle saw the U.S. as the logical and extreme expression of British ideology and strategy. The U.S. marginalized the state and, like Britain, was prepared to fight to the last European to block the Soviets. De Gaulle recalled the U.S.-British alliance in World War II, and the degree to which he had to resist having France reduced to a dominion of the United States and Britain during and after the war. The tension between Britain and the Continent didn’t end with World War II, and Britain’s relationship to the United States compounded it.

De Gaulle saw the alliance between the Anglo-Saxons as representing a multi-faceted threat to the Continent. In particular, he did not want Europe in a fixed alliance that committed the Continent to military action under certain circumstances. He didn’t want another war in Europe and was not prepared to take the same risks the U.S. was claiming it was prepared to take. He saw NATO as a threat to the EEC in many ways. He also saw the Soviets as a manageable threat, and the Americans as reckless. From de Gaulle’s perspective, then, if Britain were to join the EEC, it would act as a tool of the United States, and he was not willing to let that happen.

For de Gaulle, the cultural gap between Britain and a united Europe couldn’t be bridged. They were just too economically incompatible and their strategic interests too different.

De Gaulle’s goal in all of this, however, was not simply to build a European community. He wanted to build a European community that France could dominate, something that was still conceivable in the 1960s, while Britain remained outside the bloc. And in trying to achieve his goal, he actually anticipated the problem that would arise with the Maastricht Treaty, which established the European Union.

Britain has a very different economic and political culture than the Continent. It has a different history that gives it a different view of the Continent. Leaving other matters aside, it does not fit into Europe, and the attempt at bridging this gap has led to the worst political crisis in Britain since the fall of France.

There are, of course, many other variable to consider when looking at the current situation. Globalisation, technology, urbanisation, environmental issues have all changed the world since De Gaulle’s day but he identified key difference between Britain and the continent that still hold true. Most of them have a historical trajectory and you can see an example of this by contrasting the constitutions of Britain and Europe. Most of the EU countries have written constitutions that has been forged after conflict, whereas Britain has a mainly unwritten constitution that has evolved over time and is grounded in common law. This has evolved into the principle of parliamentary supremacy whereas, by revolution or war the continental systems have produced a stronger executive branch that can take unilateral decisions with much less constraint. We can see this in the way that Brussels, Germany and France rammed Monetary Union (EMU) through on the back of the Maastricht Treaty to consolidate national currencies into one European currency. I can remember people saying that Britain’s refusal to join reflected her attachment to the pound and empire but what made more sense was that Britain and a few other states just couldn’t see how it would work. In the end they were proved right and the fundamentals of a stable currency have still not been resolved. What was seen to be an attachment to former glory was, in fact, a practical assessment of the EU’s plans which were the product of an ideological construct and the ambitions of a politicised bureaucracy.

Britain joined the EEC which was a common market that retained decision making at the national level. I think that most British people accepted that, over time, as economies moved together so would the links between countries. The problem was that France and Germany wanted to keep up the momentum to expand the geographical community and the power of the EU establishment. The problem of keeping up the pace is that you can quickly create a disconnect between the people that you are representing and the governing body. It became very clear that the Maastricht Treaty was treated with suspicion by many countries and to counter the fears of forced centralisation the concept of subsidiarity was established. The principle of Subsidiarity does not just state that decision making be devolved to the lowest competent authority but that it is the responsibility of the central authority to make the case that it is necessary to take it away from local jurisdiction.

Specifically, subsidiarity means that proponents of centralisation are the ones who have to prove that further integration is justified. If they fail to make the case, subsidiarity means that the powers should remain de-centralised. (Making Sense of Subsidiarity: How Much Centralization for Europe?)

The authors of the 1993 report, Making Sense of Subsidiarity: How Much Centralization for Europe? clearly saw the tension between “efficiency-enhancing centralisation and democracy-enhancing sovereignty.” It also identified the principle’s weakness in that it was not defined in law and that any dispute was adjudicated by the ECJ, hardly a disinterested body. The inevitable consequence has been the expansion of Brussels at the expense of local decision making. To paraphrase Ronald Reagan, Brussels will never voluntarily reduce in size and the EU bureaucracy is the nearest thing to eternal life that this earth will ever see.

If the trade-off that Europe has chosen cannot be explained and justified to citizens, consequences are unavoidable. The loss of sovereignty can easily turn into a loss of identification with the European project, and, as seen today, the missing identification can generate a dangerous democratic deficit, and a concomitant longing for the autonomy of the nation-state.

The problem, that was clearly seen by the authors of the 1993 report , has come about. The institutions of a European wide super state are all there. The flag, anthem, judiciary, executive, parliament, external borders, membership of the UN and the beginnings of an EU military are all there to see. But who will defend this super state? Yes, we can identify the economic benefits and for some the prevailing liberal ideology but the democratic deficit that the report identified has resulted in a return to identification with the nation state that can be seen all around Europe.

Liberal governments in Continental Europe saw the Nation State as the source of all modern wars and in the aftermath of the Second World War it seemed reasonable to look for a convergence of states that would lock them together so that there would be an end to international conflict, at least in Western Europe. This would seem a reasonable strategy especially between Germany and France who between them had produced a Napoleon, Kaiser and Hitler to terrorise the continent in modern times. However, the claim that the EU and it’s predecessors have kept the peace in Europe is only partially correct. As already stated, it has stopped two member states from repeating past adventures but has it secured peace from external threats? De Gaulle’s belief that the Russians can be negotiated away have thankfully never been tested. The reason that the post war expansionist communist states were held at the western borders is NATO. De Gaulle’s nightmare had come about. It is the presence of those Anglo=Saxons that has prevented a nuclear tipped Russian advance into Paris not the EU. To be more precise, it is the presence of 60,000 U.S. troops in Europe, plus all the America military might, on call, that has held Russia in check.

De Gaulle was wrong on many fronts. Partly as a result of his humiliation during the war he incorrectly identified the main threat to post war Western Europe as being the Americans and British. However, his analysis of the differences between Britain and the continental Europeans can hardly be faulted. This means that, given the ambitions of Brussel and Paris, that the union was never going to work within the current framework. It would not fail on immigration, EMU or, the ‘great British sausage’ but on the impossibility of forcing a continental culture onto a British one. Whatever happens to Brexit the EU still has the same problems with the remaining countries and we can see the fault lines wherever you look. The problem with the model is that it attracts little loyalty from it’s citizens. Yes, we all identify as Europeans when we go through passport control but if asked where we come from we respond in national terms. We like the mobility and economic advantages when things are going well but have no accountability when things go wrong. We are told that that there is democratic control via the European Parliament but the electorate rightly sees through this myth and shows little enthusiasm for European elections. What they do see when they make a stand is that huge pressure is put on national governments to correct this aberration as happened when the Irish electorate rejected the Lisbon Treaty in the 2008 referendum. There are many things right with the EU but it is a house built on a shaky foundation and it is not clear whether this is accepted by the ruling elites or, whether they will ignore all the warnings and continue to build even higher in a desperate hope that the foundations will somehow hold.

Reference:

GPF, George Friedman, 2/04/19, geopoliticalfutures.com/brexit-charles-de-gaulles-last-laugh/

Jean-Pierre Danthine, Subsidiarity: The forgotten concept at the core of Europe’s existential crisis, 12/04/17, https://voxeu.org/article/subsidiarity-still-key-europe-s-institutional-problems