I had heard about the so-called sustainable investment ratings, otherwise referred to as the Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) rating, in general discussions about investment strategy. However, I had assumed that this was something that the Americans had invented to make their pensioners even more miserable amongst rising prices, rising crime and woke policies. Imagine my concern when I came across an article in the London FT headed, ESG Ratings Face Examination in Fight Against Greenwashing ( FT 28/05/22). It seems that it is not just an American phenomenon after all. In essence, the aim of an ESG investment is not to maximise shareholders returns but to take a more holistic view and to invest in companies that maximise stakeholders returns.

The ESG strategy means investing in companies that score highly on environmental and societal responsibility scales as determined by third-party, independent companies and research groups. “At its core, ESG investing is about influencing positive changes in society by being a better investor,” says Hank Smith, Head of Investment Strategy at The Haverford Trust Company. (Forbes Advisor)

If we lay aside the aims of ESG, as stated by Hank Smith, the thrust of the FT article was to look at the question of the quality and integrity of the ‘third-party, independent companies and research groups’ as mentioned above. The concern is that some rating agencies are providing false or, suspect data to promote companies with ratings that are misleading to investors. This is known as greenwashing. As Sacha Sadan says, “People do get surprised when they see certain stocks (such as oil and gas) in a portfolio that’s an ESG best in class … and that’s why, as a consumer regulator looking after people, we have to make sure that is correct.” (FT 28/05/22) Various government agencies and the EU are getting involved to put some standards and structure into this unregulated area with particular focus on ‘transparency, conflicts of interest and requirements to demonstrate the validity of metrics’. Before we get carried away with even more regulation, perhaps we should take note of Klasa’s observation about rating agencies in her article.

Rating agencies attracted controversy in the aftermath of the 2009 financial crisis when they gave prime ratings to highly risky mortgage-backed securities that ultimately blew up and tanked global markets. A 2011 US government enquiry concluded that the leading, “credit rating agencies were key enablers of the financial meltdown. (FT 28/05/22)

What the FT article is saying is that everyone’s definition on what is an acceptable ESG rating, is a matter of the agencies or in house departments own world view. Given that amount of ambiguity, would you buy a used car from these people?

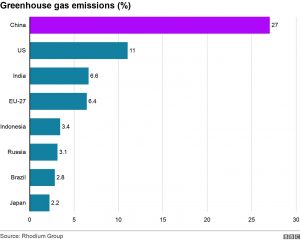

What are the basic factors that rating agencies take into account to produce an ESG score. In the first instance we have already mentioned the transition from shareholder to stakeholders return as a measure of a company’s success. According to Forbes, the stakeholders are ‘workers, communities, customers, shareholders and the environment.’ ESG proponents would argue that a positive drive to satisfy stakeholders in a company would show that it is well run and a good bet for investors. To assist in this evaluation Forbes has defined the objectives that would promote a good ESG score in the three categories. In summary, under the Environmental heading the question is, what environmental impact does the company have. This may be measured by its carbon footprint, pollution or practises that may impact on the climate. On the Social front, the company is measured on its social impact both within and outside of the company. Therefore, are it’s hiring policies diverse and inclusive. Does it support progressive groups like BLM and LGBQIA within its employees and the broader community. Governance looks at how the management is structured. Is it diverse and representative? Does it drive progressive change? I am sure that my summary can be improved on by those promoting the ESG approach but it must be obvious that, in the main, these are political objectives. The assumption is that by driving companies to achieve these social goals then you achieve the twin objectives of a more progressive community and a more profitable business. To say that most of these objectives are subjective understates the case and to assume that becoming a good ESG rated company makes you a profitable investment lacks logic. One of the biggest supporters of ESG is Blackrock and I mention it not because it is the only company promoting ESG but because its CEO, Larry Fink, is the most vocal. Mr Fink has been very vocal in his opposition to fossil fuels but has made a huge wager on the Chinese economy by investing in China’s Mutual

Fund Industry. The graph to the left shows that China’s Greenhouse Gas emissions exceed that of all developed nations combined (BBC 07/05/21). Does this not conflict with the E for Environmental part of the ESG policy he promotes? Does the fate of Muslims under the Chinese regime fit with the S for Social inclusiveness and equity segment? As for G for Governance, who knows how the Mutual Funds are managed in this respect. As reported in the Times, “BlackRock’s silence on China’s regime is particularly jarring because of its evangelical promotion of environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards. “A company cannot achieve long-term profits without embracing purpose and considering the needs of a broad range of stakeholders,” Fink said in his latest annual letter to chief executives. (The Times, 30/08/20) So far, we have a political progressive policy, that cannot be universally defined, which is hugely subjective and as we have seen, very selective and open to corruption. But is it successful as an investment strategy? To be fair, it is a little too early to evaluate with any certainty. However, logic would suggest that if our only objective was shareholder return, then it would seem that by excluding non-progressive companies, that the pool of potential profitable investments is reduced. It may be a little mischievous of me to note that the people who would make investment choices on your behalf have just achieved a new investment record. As reported by Bloomberg, Blackrock managed funds lost $1.7 trillion of its clients’ money since the beginning of the year — the largest sum ever lost by a single firm over a six-month period. Another casualty was the investment company that manages Harvard University’s portfolio which made a loss last year. In a response to questions about the loss, one of the points made by HMC was that it restricted the type of investment it made and thus reduced the possibility of a positive return. “A number of institutional investors leaned into the conventional energy sector, through either equities or commodity futures, adding materially to their total return. HMC did not participate in these returns given the University’s commitment to tackling the impacts of climate change, supporting sustainable solutions, and achieving our stated net Zero goals.” (HMC, October2022) The concept of shareholder returns is a simple and well-established concept and is easily measured. Public policy is made by elected governments and is enforced by law where interested parties can make their case. Thus, there is a large volume of employment, environmental and social law which a company must abide by. What ESG attempts to do is push a social and political policy on companies by using investors funds to vote progressive policies at AGM’s and bar access to investment by downgrading ESG scores for non-favoured companies. By doing this, Blackrock and its associates by passes public review and attempt to effect political change by the back door. If we return to the attempts to regulate this train wreck, we might extend the list of actors of whom we should be nervous. As Klas pointed out in her article, the rating agencies have a very poor record on ‘transparency, conflicts of interest and requirements to demonstrate the validity of metrics.’ The same complaint can be made of the ideologically driven green decisions made by western governments which has resulted in the energy crisis. Neither big investment companies nor governments can be trusted to regulate in favour of the man on the Clapham Omnibus.

I hope that I have brought the discussion up to date but even though I have described my problems with the actors promoting this ideology I have not stated my basic opposition to it in principle. The current status of this debate is how do we regulate the ESG policy, but I take issue with it at a more fundamental level. In my own case I have invested in a private pension after agreeing a risk factor, targeted net income and an appropriate portfolio with my pension advisor. As far as I am concerned the objective is to give me the highest income possible commensurate with the agreed parameters. I have no contact or contract with Blackrock or with any other investment vehicle and yet they use my funds to promote progressive policy. How can that be legal? Rather belatedly, this challenge has been taken up in the US.

Nineteen state attorneys general wrote a letter last month to BlackRock CEO Laurence D. Fink. They warned that BlackRock’s environmental, social and governance investment policies appear to involve “rampant violations” of the sole interest rule, a well-established legal principle. The sole interest rule requires investment fiduciaries to act to maximize financial returns, not to promote social or political objectives. (WSJ 6/09/22)

We have become so used to everyone else resolving our perceived problems that we have surrendered our rights and responsibilities as individuals. We listen to that seductive voice that says, don’t worry we are the experts, and we know what’s best for you. However, the reputation of ‘experts ‘as a class has suffered some damage over the past few years. For example, those experts who didn’t see or, benefited from, the 2009 crash. Those experts who claimed to be ‘the science’ but closed down opposing opinions during Covid. Those who supported the Tavistock Institute and their like, supplanting ideology for science and in the process doing great harm to children. We have the prospect of a cold winter and sky-high energy prices due to governments lack of any common-sense strategy in relation to green policies. The list goes on, but the message is the same. Perhaps the experts and professional classes are not so expert in matters that exist in the real world.

ESG is one example where an unpopular social change is introduced via the backdoor and suddenly, we are financing something that we fundamentally disagree with. What can we do about it? The first thing to do is to recognise that it is happening all around us. I used to be very sceptical about conspiracy theories, but lately they have an unfortunate habit of being wholly or partly true. We only need to think of the origins of Covid and how the idea that it began in the Wuhan Institute of Virology was fiercely contended for so long. I am not saying that we should review the arguments promoted by the Flat Earth Society, but we should apply the same level of scepticism to those that make decisions on our behalf in the name of the experts.

Sources

Adrienne Klasa, 28/05/22, Financial Times, ESG Ratings Face Examination in Fight Against Greenwashing, p15

E. Napoletano, Benjamin Curry, no date, Forbes Advisor, www.forbes.com/advisor/investing/esg-investing/

Report: China emissions exceed all developed nations combined, 07/05/21, BBC, bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-57018837

and

,N.P. “Narv” Narvekar,October 2022,Harvard Management Company,/finance.harvard.edu/files/fad/files/fy22_hmc_letter.pdf

Emma Dunkley, 30/08/20, The Times, Larry Fink, thetimes.co.uk/article/larry-fink-blackrocks-ethical-investment-evangelist-kowtows-to-beijing-wqt6hs3jp